Part 2 of An Introduction to Stoicism: Why Other People Cannot Harm Us.

In Part 1 of An Introduction to Stoicism, we discussed the Dichotomy of Control, which tells us two important things:

That anything outside of our power is indifferent

That the only thing within our power is our choices.

This means that anything besides our actions and choices are without value to us and do not benefit or harm us. Be it money, pain, fame, or a successful career, the Stoics considered all of these things to be outside of our power, and thus indifferent to us.

At first glance, this may seem to be naïve or wishful thinking on the part of the Stoics. Sure, it would be nice if all the things I do not control did not matter to me, but they really seem to matter. If I get punched in the face, that was not my choice, but it still seemed to harm me. If I am let go from my job for something that was not my fault, and go hungry, I seem to have been harmed by something outside of my power. At its worst, Stoicism seems to be just an anesthetic, a means to rationalize away or numb the pain of the harms I cannot control, in order to give me the energy to focus on the things that I can control. In other words, Stoicism can appear to be helpful but false.

Fortunately for us, Stoicism has arguments about why a punch to the face is not harmful to us. But to understand them, we must examine what Stoicism thinks a person is.

Our essential self as our free choice:

Stoicism argues that what we fundamentally are is our hegemonikon or ruling-faculty. The ruling-faculty considers information, and then makes a decision about how to act based on that information. As such, it can be roughly understood as our faculty of choice. We are just this choice and nothing else. We are not our possessions, our reputation, or even our body, but just this capacity to reflect upon information, and make a decision.

This faculty of choice is understood to be free. This means that it cannot be forced by anyone to make any kind of decision. Choices then are within the power of the individual. But the Stoics believe that this is the extent of our freedom. These choices are the only thing we have power over. I can choose to do something, but I have no control over whether or not I succeed. That is determined by other factors, by things external to me. So I can choose to try and apply for a job, or catch the next bus, or ask someone out on a date. But whether or not that goal is successful is not within my power. It depends on things beyond my choice, such as the biases of the hiring committee, or whether or not that bus is late or early.

However, since we are our choice, and not our bodies nor our reputations, if our choice is free then we are free. Nothing can force me to do anything but my own choice. Someone can kidnap my body or burn down my house, but they cannot make me choose to do anything unless I agree.

This conception of identity helps to explain why externals objects are indifferent. If I get a nice car, how has this benefited me as I essentially am? This may help my reputation, but that is not what I am. If someone hits me, how am I harmed? This may hurt my body, but I am not my body, I am my choice.

The only things that can harm the individual are bad choices. Likewise, the only things that benefit the individual are good choices. What good and bad choices consist of will be the topic of another article, but generally bad choices are ones based on ignorance, and good choices are those based on truth. So to be cowardly in the face of physical danger is a bad choice, because I am ignorantly considering physical threats to be harmful, when they are in fact indifferent. Similarly, to not be offended by an insult would be a good choice, because it demonstrates your understanding that this insult is indifferent to you.

Why other people cannot harm us:

A major benefit of understanding the self as our free choice is that other people cannot harm us with their actions. This is because other people only have the ability to act upon and influence things external to us. So someone can threaten my body with violence, but they cannot control, determine, or shape my choice. They can follow through with that threat, and harm my body, but they still have not influenced my choice, and thus not harmed me as I fundamentally am.

This can seem very counter-intuitive at first. One would think there is a direct cause and effect between someone’s actions, and them harming me. If they insult me, I am angry. If they threaten me, I am afraid. If the steal from me, I have less. How can we claim the other person is not the cause of this harm?

The Stoic response to this is that in the above examples we ourselves are the cause of the harm. Specifically, we harm ourselves through our poor choice to view this person’s actions as harmful. We are harmed when someone steals from us, only when we think these possessions are beneficial to us and we desire to have them. If we remove that incorrect view, the suffering is removed as well.

The Stoics had a simple but profound analogy to explain this. Imagine a rectangle and a sphere. If I push both, the rectangle barely moves, but the sphere will roll. What is the cause then of the sphere rolling? Most people would say the push, but this is a mistake say the Stoics. The cause is the shape of the sphere. Change the shape, and the same input has an entirely different output. So we, as humans, must recognize that we have control over our shape. We cannot blame the push for our suffering when we are choosing to be spheres. We must look instead to transform ourselves.

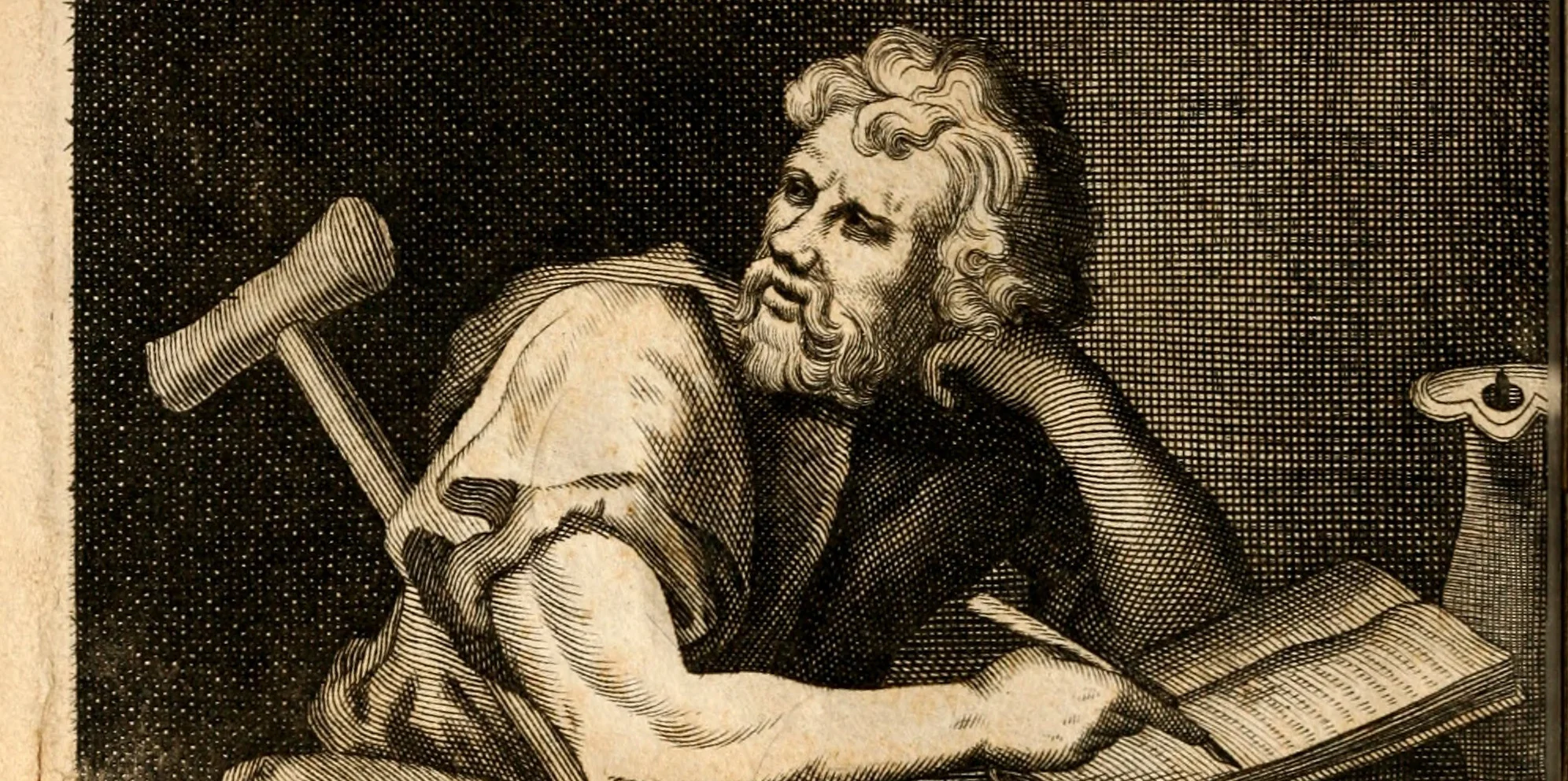

Consider one of my favorite quotes by the Stoic Epictetus who aptly summarizes how important it is to remember in moments of struggle that we are just our choice:

“What then should a man have in readiness in such circumstances? What else than this? What is mine, and what is not mine; and what is permitted to me, and what is not permitted to me. I must die. Must I then die lamenting? I must be put in chains. Must I then also lament? I must go into exile. Does any man then hinder me from going with smiles and cheerfulness and contentment? Tell me the secret which you possess. I will not, for this is in my power. But I will put you in chains. Man, what are you talking about? Me in chains? You may fetter my leg, but my will not even Zeus himself can overpower. I will throw you into prison. My poor body, you mean. I will cut your head off. When then have I told you that my head alone cannot be cut off? These are the things which philosophers should meditate on, which they should write daily, in which they should exercise themselves.” (Epictetus, Discourses, 1.1)

In conclusion, Stoicism asks us to remember ourselves as we essentially are. And to examine what is good or bad for this essential self. This is a helpful exercise for everyone. Even if you disagree with the Stoic conclusion of what we are, we can agree that we often extend our concern too far. All too often we put our identity into our possessions, into our reputation, into our professional aspirations, and of course into our body. We think we do well when these things do well, and we are harmed when these things are harmed. But Stoicism tells us that we are not these things. We are only our capacity to make choices. So the only thing that can harm us is bad choices, and the only thing that can benefit us is good ones. And, fortunately for us, no one has power over the choices we make but ourselves.